|

Posted at 12:42 am on January 24, 2012, by Eric D. Dixon

Public choice article of the day, from The Atlantic:

To be clear, although I’d like to avoid the consumption of antibiotic-treated livestock as much as possible, I don’t think the FDA should ban it — a clear overreach of government power.

If the FDA allows a product or practice, the public at large regards it as safe. If the FDA disallows something, society assumes danger. But instituting a top-down decision-making process to centralize the level of risk that consumers should be allowed to take leads to a system that serves nobody well. Life-saving drugs are barred from being used by people who are more than willing to accept their potential hazards. The sale of healthy food is criminalized because of the mere possibility that it could make somebody sick, despite the fact that people can and do get sick from the FDA-approved alternative. And, as shown in The Atlantic, because people trust that D.C. paternalists are looking out for them, they carelessly consume anything that the FDA has let slip through its otherwise iron grip. A bureaucratic overlord is incapable of choosing the correct balance between risk and reward even for the people in his neighborhood, let alone for more than 300 million strangers scattered throughout the country. There is, however, an alternative, as Larry Van Heerden noted in The Freemam:

[Cross-posted at Shrubbloggers.] Filed under: Corporatism, Drug Policy, Food Policy, Nanny State, Public Choice, Regulation Comments: 2 Comments

|

|

Posted at 12:10 am on December 10, 2011, by Eric D. Dixon

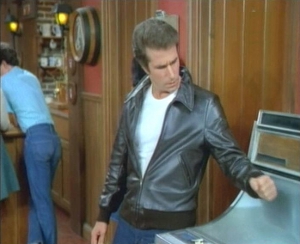

The Fonz could knock down doors with a slap of his hand, summon any girl with a snap, and most often on the show displayed his classic power of fixing the jukebox by banging on it. It’s a seductive fantasy that one might be able to fix a complex piece of machinery through an application of blunt force, without having to worry about the intricate mechanisms that actually allow the machine to work. Unfortunately, this is the mentality that has reigned for decades in applied public policy. Is the economy broken? Bang on it. That’ll get it chugging along again. Wait, that didn’t work? You didn’t bang it hard enough. Or maybe your leather jacket needs to be a little cooler next time. At any rate, it’s your fault. If you’d only smacked the economy the way that Fonzie showed you, it totally would have worked. Economic prescriptions thereby stem from a non-falsifiable tenet of faith in a grown-up power fantasy. This kind of magical thinking convinces many because it is accompanied by a veneer of rigorous thought. There are even equations! Surely, equations are scientific! But as economist Don Boudreaux pointed out at Cafe Hayek:

Keynesian macroeconomic variables lump heterogeneous goods and services into undifferentiated masses, no longer to be understood as the complex workings of a dynamic system of social cooperation. But just because you can gather a bunch of statistics and aggregate them into a variable doesn’t mean that the variable has a meaningful application to the real economy. If you want to fix a jukebox in real life, a mechanic might be able to get the job done by tinkering with the machinery until each piece once again functions correctly. It’s easy for people who have a facility with physical forms of engineering to take a similar view of the economy, thinking that if only the right people were in charge, they could tweak policy here and there to ensure successful outcomes for everyone. Adam Smith explained why the economy can’t be successfully engineered in such a way:

Even though an economy can’t be planned, or even tailored, successfully from on high, that form of scientism is at least understandable. It at least takes into account a small measure of the complexity of decentralized economic activity, even if it doesn’t — indeed, can’t — consider the rest. Keynesian macroeconomics is far worse, shunning even the scientistic attempt to grapple with at least some heterogeneous microeconomic factors as being the causal source of economywide trends. Instead, they insist that policymakers expropriate as much cash as humanly possible and wallop the economy with it as hard as they can. Economist Steven Horwitz summed up the real prescription for economic recovery:

In the end, the economy is not a jukebox, and neither a mechanic nor Ben Bernanke in the coolest leather jacket ever made can save it from its turmoils. Instead, the economy is made up of hundreds of millions of people with billions of plans, many of which fail but some of which succeed. Nobody knows for sure which plans will pan out in advance — not the people making them, and certainly not their public officials. Only by letting individuals, alone or in voluntary association with others, respond to local conditions with unique knowledge can the best plans be discovered, expanded, and replicated. That process is made much more difficult when they face continual interference from central planners who only pretend they can know what’s best. [Cross-posted at Shrubbloggers.] Filed under: Economic Theory, Efficiency, Government Spending, Market Efficiency, Regulation, Spontaneous Order, Unintended Consequences Comments: 1 Comment

|

|

Posted at 10:30 am on November 6, 2011, by Justin M. Stoddard

First, allow me to clarify a few points about the video below before I start into the meat of the matter. The video is obviously edited — for what purpose, I do not know. It could have been to cut down its length or to stitch together a narrative that puts the person being interviewed in the worst possible light. Though, admittedly, given his statements, I don’t know how that’s possible. I understand that people who are put on the spot with a camera in front of their face are going to stammer and search for words. After seeing thousands of these kinds of videos, I’m convinced that people generally do not do well when confronted with on-the-spot interviews.

There are some awkward questions that need to be asked in response to this assertion. Besides the obvious catchy “one percent of the people own 43 percent of the wealth” trope, why not move that arbitrary line to the top five percent? If the top one percent own 43 percent of the wealth, wouldn’t it follow that the top five percent own even more of the wealth? How about the top ten percent? The top 25 percent? The arbitrary line is chosen because it fits nicely into the idea of the proletariat struggling against the bourgeois. What is being insinuated here is the top one percent own the means of production while the 99% are the factors of production. How is the “1 percent” being defined here? One percent of the population of the United States or of the population of the world? The question matters a great deal, for a couple of reasons: One percent of the population of the United States is a little more than 3 million people (approximately the population of Mississippi). Just playing the numbers game, it strains all credulity to accept the assertion that the more than 3 million people being referenced here don’t produce anything. One percent of the world’s population is about 70 million people (approximately the population of California, New York, and Ohio combined). Of course, this takes credulity to the breaking point. The question hardly needed to be asked. The only population statistic being used here is the population of the United States. The OWS crowd skirts over the fact that if they were to count the entire population of world, the majority of them would end up in the top 1 percent of people who control wealth. That’s simply an argument they dare not broach. I’ve addressed this briefly here, but I’ll expound on it just a bit. Even adjusting for purchasing power parity, if you make $34,000 or more per year, you are in the top 1 percent of world income earners. Income disparity between someone who makes $34,000 and someone who makes $500,000 per year in the United States seems pretty significant, but not nearly as significant as the income disparity between someone who makes $34,000 per year in the United States and someone who makes $7,000 dollars per year in India, or $1,000 per year in Africa. The standard argument against this line of reasoning goes like this:

Lest I be accused of making up my own argument to refute, that’s a response I got on a recent Reddit thread addressing what I said above. At first blush, this makes quite a bit of sense. Commodities do seem to be more expensive in the United States than they are in the Sub-Sahara (unless you are living in a country with hyper-inflation). Earning $1,000 per year will certianly not give you the purchasing power to buy or rent a house or an apartment. You may or may not be able to afford transportation. Food and clothing would also be difficult to acquire. But, one is tempted to ask; would you rather live in the United States with an income of $1,000 per year or in Sub-Saharan Africa with an income of $1,000 per year? Here are the two main problems I see: First: The United States (and other First World countries) have many orders of magnitude more consumer goods and commodities to choose from than all of the Sub-Sahara put together. In the United States, $1,000 goes much further because there is so much more you can do with it. You must also consider basic welfare entitlements to every poor citizen in the United States to be used for food, shelter and clothing, along with other factors of income like child support payments and not being required to pay taxes. It further discounts the ability to barter for goods, rely on charity, and utilize the cast-offs of the rich and middle class. Our country is awash with high-class “junk.” It is very easy to acquire clothes, furniture, gadgets (TVs, microwaves, phones, radios, etc.) just by asking for it. It’s unbelievable how much stuff the well-off just leave on the curb for others to pick up. Whole virtual communities like Freecycle and Craigslist thrive around the concept of either exchanging these types of goods or just giving them away. If you are savvy enough, it is possible to get hundreds of dollars worth of name brand products for free through the practice of extreme couponing. There are literally hundreds of blogs dedicated to the concept of extreme frugality, meaning there are people in this country who choose to live well below the poverty line by recycling, reusing, budgeting, couponing, growing their own food, bartering, etc. From all accounts, they have healthy and happy lives. Second: If you take all other factors into consideration, even for those at the very bottom of the socio-economic scale, life is comparatively much better here. On average, people in the United States live 20–35 years longer than those in the Sub-Sahara. In America, there is an infant mortality rate of eight out of every 1,000. In Mali, the rate is 191 out of 1,000. While millions have perished in Africa because of famine, I have not been able to find any account of a single person starving to death in America because of an inability to acquire food. There are rare cases in which people are starved through abuse or neglect, but the issue of general access to food was not a factor. On the contrary, we are constantly reminded that we have an epidemic of obesity in our country. Looking at population statistics, this is a problem that affects the poor almost exclusively. Millions more have been butchered in war, slavery, and genocide in Africa during these past 20 years. With the exception of 9/11, war, slavery, and genocide have killed exactly nobody in America — unless you count the “War on Drugs.” (I’m excluding here our military adventures overseas — which both liberals and conservatives love — and focusing on civilian deaths within our borders. More than 1 million people die from AIDS/HIV in the Sub-Sahara each year. Nearly 2 million more contract the disease yearly. The region accounts for about 14 percent of the world’s population and 67 percent of all people living with HIV and 72 percent of all AIDS deaths in 2009. Contrast that to the United States, where there are approximately 1 million people infected with HIV. About 56,000 new people become infected each year, while roughly 18,000 per year die from AIDS. Even the poorest of poor in America have the means and ability to protect themselves from sexually transmitted diseases that ravish other populations. This represents just a cursory look over publicly available data, of course, but many inferences can be drawn. Living off $1,000 per year in the United States is actually a lot easier than living off of $1,000 per year in the Sub-Sahara. In the United States, $1,000 per year still makes you pretty well off compared to a huge majority of the world’s population. Instead of the OWS asking why this is the case (different economic and political policies have different economic and political outcomes), they are insisting that it’s not the case, in the face of all empirical evidence. It’s a complete break with reality. All of this begs a basic question. We know that there are millions of people living in Africa on $1,000 per year or less, but are there people living on $1,000 per year in America? Maybe. According to the 2008 United States Census, the number of individuals living on $2,500 or less is 12,945. If you count households instead of individuals, that number drops to about 3,000. Looking at demographics, we find that many of those either live on Indian reservations or in closed off religious communities. The vast majority live in very rural areas, with the exception of some communities in Texas and California. This brings up another awkward question. Can we differentiate between the worthy and the unworthy poor? Is it safe to say that those living on an Indian reservation are most likely the victims of centuries of oppression, paternalism, and other factors beyond their control, and deserve our sympathies, while those whose religious doctrines call for unsustainable familial and community growth (though still collecting welfare entitlements) don’t? Back to the original point. Taking this all into consideration, the speaker (along with 70 million of his fellow human beings) is more than likely in the top 1 percent of income earners in the world. Does he produce nothing? Do the other 70 million people produce nothing? If he had a shred of intellectual honesty, he would advocate taxing anyone who makes $34,000 per year or more at a very high rate so that money can be redistributed to the absolute poor in Africa, India, China, Afghanistan, etc. If you’re going to advocate forced redistribution, what’s the more moral course of action? Paying off student loan debt and making secondary education free for those who are extraordinarily rich in comparison to world standards, therefore giving them further opportunities to collect more wealth, or giving that money to someone who will quite literally starve to death without it?

Even though you can tell he’s searching for the concept, what he’s attempting to recall is the Labor Theory of Value, which suggests that the value of goods derives from their labor inputs. Some take it a step further and suggest that goods should therefore be priced according to those labor inputs rather than in response to the demand for those products. This murderous idea has been refuted too many times to count and isn’t taken seriously by mainstream economists. As with the devastating yet simple argument against Pascal’s Wager, this is a case of rudimentary logic pitted against religious thinking. If a laborer labors all day making mud pies instead of pumpkin pies, he may well have put in a great deal of work, but still produces absolutely nothing of value. Not understanding why someone would do that, I come along with a novel idea. Why not hire that labor (which is obviously motivated to work) and have him make pumpkin pies instead? Which is more valuable, the labor or the idea that moved the labor in a profitable direction? Given time, one of my workers gets a workable idea that it will actually make it more time- and cost-efficient to divide the labor and go into business for himself making ready-made pie crusts to sell back to me. In turn, he hires 10 more people. Another person figures out that growing local pumpkins for production is not sustainable or efficient, so he saves his capital and starts an import business to buy pumpkins to sell back to me. In turn, he hires 10 more people. Of course, that import company creates demand from pumpkin farmers halfway across the country, signaling to them that they need to hire more people. But what about packaging? How will I wrap all those pies? Where will I get the metal for pie tins? How do I even make a pie tin? What if I want to branch off into cherry pies or apple pies? What if I want to sell coffee with those pies? The Labor Theory of Value is an epic failure of imagination. At any given moment, there are two types of birds on the face of the earth, those that are airborne and those that are not. Do you know what the number of birds in each group will be, say, 10 seconds from now? The answer may well be impossible to ever figure out, but there is an answer as concrete and real as the computer screen you’re looking at. It will take a great deal of dispersed observation, knowledge, and computer power to ever figure out the answer to that question, but it takes an even greater amount of imagination to think of a use for the question in the first place. On the labor side of the equation, how many people per day, independent of each other, not even knowing of each other’s existence, were involved in making Steve Jobs’s ideas a reality? Can you imagine it? Can you even begin to try to imagine it? When you do, dig deeper. When you do that, dig deeper still. You will find yourself trying to comprehend a voluntary network of a number beyond your comprehension all working independently but in concert with each other in order to make that idea a reality. The vast majority have no earthly idea that they are working toward a common goal. If you’ve read the essay “I, Pencil,” you can start to grasp the amazing complexity of what goes into creating one simple product. Once you’ve started to grasp that concept, you realize that an iPhone or a Macbook is nearly infinitely more complex than a pencil. When you think you have a grasp on all of that, add into the mix all the competition that Steve Jobs inspired in the economy. Microsoft, Google, Android, Unix, Linux, smart phones, laptops, programming, software and hardware development, battery efficiency — the list goes on and on. Multiply everything above by factors unimaginable when you add in each new facet of competition. How many people were involved in making Steve Jobs’s ideas a reality? Like I said, there is a concrete answer to this question. I don’t doubt that computers will some day be able to figure it out. I’m not confident that it will ever happen in my lifetime. However, if you are able to imagine the several billion neurons in your brain exchanging countless bits of information each second, culminating in what we call human consciousness, then you are getting close to the complexity involved in the network of voluntary exchange Steve Jobs helped put into motion. Now think of the consumer side of the equation. For the purpose of this example, let’s limit ourselves to the latest model iPhone. For about $199, plus a two year contract with a cellular phone company, you can walk out the door with an iPhone 4S. Putting aside for a moment all the apps you can use, these are the features that come built in, off the shelf:

Another exercise in imagination, if you will: Consider every bit of technology listed above (we will ignore the wonderful advances in lithium battery, sensor, and storage technology for the purposes of this exercise) and the infrastructure needed for it to work. Now take it back in time just 20 years, to 1991. Keep in mind, all of this wonderful technology is crammed into 4.5 by 3.11 by 0.37 inches, with a total weight of 4.9 ounces. How much would something with comparable functionality cost back then? The logical answer would be that the technology did not exist 20 years ago, so it would be priceless. But this is a thought exercise, so we can at least break down some of the components and price them individually. In 1991, the most common portable analog phone (cell phone technology was still in its nascent stages) was a Motorola MicroTac 9800X. It was lauded for its compact size, and for being the first flip phone on the market. It was an inch thick and nine inches long (when opened), and weighed close to a pound. The only thing it did was make phone calls. The quality of the calls were reportedly pretty bad. You couldn’t use the phone while traveling outside your metropolitan area, and it was pricey to make any phone call. It sold for anywhere between $4,153 and $5,822 in current dollars (adjusted for inflation). The first digital camera was released in 1991. It was a Kodak Digital Camera System, and had a resolution of 1.3 megapixels. It also came with a 200 MB hard drive that could store about 160 uncompressed images. The hard drive and batteries had to be tethered to the camera by a cable. Cost in current dollars, adjusted for inflation: $33,317. This is where I stopped. At just two laughingly inefficient components (according to today’s standards; back then, they were miracles of technology) in comparison to what comes standard on any iPhone available for $199, I was already hovering around an overall price of $40,000. Extrapolate all of that out, including all the infrastructure required to make it work, and you can easily conclude that literally all the money in the world in 1991 could not buy you an iPhone. Today, I can walk into a store conveniently located near me and get a device that makes it nearly impossible for me to get lost, lets me communicate with people I’ve known my whole life who are scattered all over the globe, allows me to take wonderful pictures and record moments of my life, provides access to all the information available on the Internet, streams any number of movies or TV shows directly to me, tells me an extended forcast, lets me video chat with my daughters and phone anyone I wish, along with any number of other things — all for the paltry sum of $199 and the price of a two-year contract. A product that Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, the Queen of England, and any royal prince would be unable to purchase 20 years ago is now as ubiquitous as the air we breathe. That’s what Steve Jobs produced. And, as a bonus, the wealth created by his idea provided the means to countless other people around the world to purchase what he produced.

This pretty much speaks for itself. In this guy’s preferred system that disallows voluntary economic association, in order to get from point A to point B, a whole lot of murder, mayhem, theft, and rape will have to occur first with an end result of abject poverty for hundreds of millions of people.

There’s quite a bit of political philosophy that can be addressed here, but the next question pretty much sums it up for me.

This is a brilliant rejoinder. Popular democracy is nothing more than mob action. If everything is up for a vote and decidable by the “will of the people,” then there can be no individual rights, ever. The individual will always lose. The argument I often hear in support of popular democracy goes a little something like this: Wouldn’t you vote against Hitler to keep him out of power? Well, the very fact that someone like Hitler can run for an election tells me that the system is completely invalid. If the election is deemed valid and workable because he weren’t voted in, it would be just as valid and workable if he were voted in. That’s the long answer. The short answer is, “No, but I’d gladly shoot him in the face.” Even the OWS crowd seems to understand that popular democracy is basically the rule of the mob, because they have set up rules in their assemblies dictating that 100 percent consensus must be reached before anything passes. But that just makes the mob smaller.

An argument from belief is a religious argument. Also, framing an argument based on what you think that other people “need” is highly paternalistic. At worst, if carried out to its logical conclusion, this line of thought is murderous, if not genocidal. What is not acknowledged or understood here is the notion that a person’s talents and particular genius are priceless. A person’s talent and particular genius is nearly the whole sum of a person. Disallow a person to use his talents or genius in voluntary association with others, and you’ve essentially murdered his spirit. You’ve destroyed the greatest resource on the face of the earth, and it can never be replaced. Ever.

I’ve already eviscerated this notion above. It obviously does work. It obviously does not create mass unemployment or poverty. It obviously does not create war. In three minutes time, this person said he would do the following if he were in power:

None of this can be done without a whole lot of guns and a whole lot of cold-blooded murder. And in his mind, Steve Jobs creates war, poverty, and unemployment? I’ll just put these few examples here.

Combined with all other genocides, wars, famine and repression caused by national governments, the death toll for the 20th century is approximately 160 million. If you took half of the population of the United States (every other man, woman, and child) and shot them in the head, you would have the number of people murdered by governments, the majority of whom were killed by their own governments.

Of those 160 million murdered, how many may have turned out to be like Norman Borlaug, the man credited with saving up to 1 billion people worldwide from starvation? For those of you counting, that’s one seventh of the world’s current population. Can one honestly confront that number and still insist that talent and genius are not important? That free association should be done away with? That mob rule should prevail?

As Billy Beck brilliantly said when he linked to this video on Facebook, “Have you ever seen a man cut his own throat with philosophy?” Well, dear reader, you just have. [Cross-posted at Shrubbloggers.] Filed under: Corporatism, Economic Theory, Efficiency, Gains From Trade, Labor, Market Efficiency, Philosophy, Property Rights, Regulation, Rhetoric, Taxes, Trade, Unintended Consequences Comments: 1 Comment

|

|

Posted at 12:05 am on October 19, 2011, by Eric D. Dixon

Here’s a great cartoon from Completely Serious Comics published earlier this year, currently being passed around on Facebook by critics of Keynesian stimulus: I doubt the cartoon’s creators were thinking about government stimulus of aggregate demand when they conceived this, so it has become a piece of appropriated satire. And, like pretty much all great satire, it doesn’t play completely fair with its target. Even so, it contains a substantial nugget of truth. Readers of this blog who are familiar with the book from which it takes its name will be well-acquainted with the broken window fallacy, first created as a parable by Frédéric Bastiat and later appropriated by Henry Hazlitt, who applied it to a mid–20th century economy. In a nutshell, the parable explains why destruction doesn’t make a society wealthier. It may stimulate short-run economic activity as people rush to replace and rebuild what they’ve lost, but always at the expense of overall prosperity. Within the past few years, Bastiat’s and Hazlitt’s critical heirs have applied the fallacy again and again to modern Keynesians. Here’s a video that does exactly that to Paul Krugman’s application of Keynesian theory to the destruction wrought by terrorist attacks (featured on this blog last year): One objection to this line of thought could be that the broken window parable doesn’t apply to general stimulus, because government spending absent a disaster isn’t the same thing as destruction, and so isn’t analogous with a broken window. One response to this objection would be that the broken window parable is part of a larger essay about the unseen effects of various types of economic action. People explaining the arguments in the larger essay, which does indeed include government spending, might reasonably refer to them by invoking the best-known portion of that essay, the parable of the broken window. Conjuring the whole of an essay by referring to one part would be a kind of allegorical synecdoche, if you will. Another response would be that spending may not destroy useful physical objects, true enough, but it does divert resources from more productive to less productive uses. Although private-sector businesses can’t be sure what their most productive potential investment will be, the government is by nature even less informed and therefore less capable of investing wisely. Siphoning resources from the private sector to the public sector destroys wealth, even if it doesn’t destroy specific goods. An allegory of a destroyed object certainly applies to the reality of destroyed wealth. Keynesian apologists, and even some non-Keynesians, have cried foul in still more nuanced ways, pointing out that advocates of government stimulus don’t per se want destruction, and may not even think it will bring increased wealth, but think instead that it will increase short-term economic activity, increasing employment and smoothing over economically troubled times. There are indeed shades of meaning and intent here. Believing that destruction may benefit the economy in some structural way, thereby sustaining short-term damage for long-term gain, isn’t the same thing as thinking that any individual act of destruction will increase economic wealth. After all, as Joseph Schumpeter pointed out, entrepreneurs engage in short-term “creative” destruction all the time, writing off temporary losses as a necessary cost of pursuing their visions for long-term productive investment. The evidence, however, shows that government spending intended to stimulate the economy and smooth out the business cycle instead exacerbates the business cycle, leading both to higher peaks and lower valleys. As Russ Roberts pointed out at Cafe Hayek:

When there’s a downturn in the business cycle, there’s a structural problem with the economy — too many people in some occupations, not enough people in others. General stimulus provides no economic information about where people should go to find sustainable productive work, meeting real demands by providing the goods and services that people want rather than the trumped-up illusory demand prompted by government spending. You can’t build a healthy body on a string of sugar rushes, and you can’t build a healthy economy on a series of artificial top-down influxes of cash. Stimulus only spurs some sectors of the economy by dampening others, whether present or future. The more that government officials tamper with the economic signals that let entrepreneurs know when they should invest and when they should steer clear, the more skittish investors become. Regime uncertainty entrenches malinvestment, and keeps the economy limping along. So, Keynesians, please stop celebrating destruction as a cure for economic ills. If truly creative destruction needs to happen in order to move less productive resources into more productive uses, private-sector entrepreneurs have the decentralized knowledge necessary to determine which of their own resources need to be replaced or reshuffled. Government officials do not. The only real cure for our lagging economy is for the government to quit breaking windows. [Cross-posted at Shrubbloggers.] Filed under: Economic Theory, Efficiency, Government Spending, Market Efficiency, Regulation, Spontaneous Order Comments: 1 Comment

|

|

Posted at 1:15 pm on November 1, 2010, by Sarah Brodsky

A friend of mine recently applied for an off-air position at a radio station. The interview went well–until they asked if he were a Christian. When he said he wasn’t, they responded that they were sorry, but they were running a Christian talk station and they could only hire Christians. They said that they had to have this policy in order to comply with FCC regulations. That seemed pretty bizarre. I could understand a Christian station wanting to hire people with similar beliefs, but what did the FCC have to do with it? Then I looked up the FCC’s Equal Employment Opportunities regulations. The FCC requires stations to do a lot of things to avoid discrimination in recruitment. They have to participate in job fairs, sponsor job fairs, host job fairs, offer internships, or take other actions that have been approved by the FCC. All of those measures impose some costs on stations. However, a religious station need not take these steps to recruit for an open position if it makes religious belief a qualification for the position. So to keep their recruitment costs down, Christian stations bar non-Christians from employment. Rules that were supposed to prevent discrimination are actually causing stations to discriminate. The religious discrimination might even out, so to speak, if there were equal numbers of stations affiliated with many different creeds. But of course, the vast majority of religious radio stations are Christian. There are very few Muslim stations or Jewish stations; I’ve come across online Buddhist broadcasts, but no brick-and-mortar Buddhist stations. And I haven’t found any atheist radio stations, although there are individual shows dedicated to atheist ideas. A Christian who wants to work in radio likely won’t miss out on any opportunities, but a Muslim or an atheist will be passed over when religious stations are hiring. Would that happen even if the FCC didn’t impose these regulations? Not necessarily. I’d expect Christian stations to exclusively hire Christian for on-air positions. And probably they would want only Christians to write content for religious shows. But there are other jobs, like board operator or call screener, that people with different beliefs could still perform competently. Religious stations might hire people of other faiths for those roles, if the FCC didn’t give them an incentive to discriminate. Filed under: Regulation, Religious Freedom, Technology, Unintended Consequences Comments: Comments Off on How the FCC Encourages Religious Discrimination

|

|

Posted at 10:06 am on August 11, 2010, by Lee Sharpe

What is “net neutrality”? Net neutrality is government regulation which prohibits internet service providers from diffrentiating internet traffic based upon its content and/or the service being used. Advocates are concerned about internet service providers charging different amounts for different types of traffic or manipulating how internet traffic is processed so, for example, to increase the priority of a certain website’s traffic or decrease the priority of a certain website’s traffic. Generally, regulation advocates point to something happening, identify it as a problem that government needs to solve, and propose regulation they feel will accomplish that goal. This is not the case with net neutrality because right now internet service providers are voluntarily complying with the standards net neutrality advocates seek to codify. This is even after a federal appeals court ruled in Comcast v. FCC that the FCC (at least currently) lacks the authority to prevent companies from engaging in this behavior. Given all of this, one must wonder why is regulation needed to address this in the first place. Like many other newspapers, the New York Times runs advertisements. The newspaper and advertiser agree on the ad, where it will appear, how much it will cost, and on which printing(s) it will appear. All well and good. And, of course, the New York Times can reject any ad which it does not wish to run. The reason could be because the content is inappropriate for the paper’s readership. It could be because it advertises a competing newspaper. It could be because the editor has a random grudge against a local business and won’t support its ads. Whatever the reason, the New York Times has the freedom to not run certain advertisements. The freedom to refuse to facilitate speech one doesn’t like is part of one’s First Amendment freedom of speech rights. There is no reason this right should not carry over to internet providers as well, just like any other entity. Many airlines offer passengers who pay for a “first class” ticket improved service for extra money. This extra service is for those willing to pay more. In addition to covering the costs of providing the extra service, this revenue helps the airlines lower fares for the other passengers, so its existence helps them as well. Similarly, television providers (both cable and satellite) offer various premium channel packages for extra fees. Nothing is wrong with these business models. Of course, nothing is wrong with a business model that handles all traffic equally either. Supply and demand will determine which business models are best just fine, just as described above in the airline and television industries. Congress and the FCC do not need to enforce a particular business model on internet service providers, as it might end up that way in the future. It’s entirely possible that at some point poorer consumers will be served by options of cheaper, more limited internet. Under net neutrality, however, internet service providers would be prohibited from pursuing such plans. Logically, companies in any industry don’t want to be regulated. So it should cause one to pause when companies in an industry come out in favor of them being regulated. Google and Verizon Wireless did just that in a recent joint proposal to the FCC as a suggestion for how to implement Net Neutrality. In the first four of their seven points, Google and Verizon start off sounding like they support their own regulation. (“This means that for the first time, wireline broadband providers would not be able to discriminate against or prioritize lawful internet content, applications or services in a way that causes harm to users or competition.”) However, the fifth and sixth create a couple exceptions to their Net Neutrality propsals for “additional services” (it’s unclear how this is defined) and internet service provided wirelessly. Now that we’ve examined their proposal, we should ask why would they propose it in the first place? The answer is to gain an advantage over its competitors, an example of behavior known as rent seeking. Businesses can and will use not just market advantages to seek profit, but legislative advantages if it can create them. Verizon is already a leader in wireless internet service, and with its FIOS technology and Google’s constant innovations, it seems like these rules are being constructed to create an advantage over more traditional internet service providers which use DSL or cable lines and would thus be subject to the net neutrality provisions while Google and Verizon are comparitively less regulated. The common response to this by net neutrality advocates is to reject the Google and Verizon plan and adopt a stronger one instead. Indeed, this is already happening by some advocates. History shows, however, that industry is heavily involved in the regulatory process and puts heavy pressure to implement them in its favor. This is common with regulation, since the benefits to a single given consumer from net neutrality are relatively minor, while the costs are borne by the companies. Since these internet service providers don’t really care about much except internet aceess, they have lot of reason to lobby and shape the regulation to their advantage, and bigger providers have more resources to do this. Consumers care, but it is a small fraction of things they must worry about in their lives, and give the legislation little attention. This results in regulation that hurts consumers by distorting the industry away from customers’ true preferences. For example, exempting wireless from net neutrality may mean that cheap wireless limited internet plans exist, while even cheaper cable ones legally can’t, which hurts consumers seeking this type of plan. The net result of all of this is the FCC implementing policies that actually have significant support from within the industry. However, if the regulation was actually achieving its goals, this regulation should actually be opposed by the industry. If the government regulates net neutrality, policies for internet access are set by one entity: the FCC. However, if the government stays out, each company will set its own policies. If you don’t like the FCC’s policies, you are stuck with them unless you leave the United States. If you don’t like your internet service provider’s policies, you can simply switch to another one. So which model sounds better to you? Update: The Electonic Frontier Foundation is also worried about the phenomenon I descibed above (Hat Tip to @wilw):

Filed under: Internet, Regulation Comments: 85 Comments

|

|

Posted at 12:24 am on July 30, 2010, by John W. Payne

There is a brief but important article in Wired on how regulations designed to protect small investors have made it impossible for them to seek out attractive investments in non-public companies, and it’s worth quoting extensively:

I get very tired of saying this, but it will never cease to be true, so I will keep at it: the government is the primary tool by which the rich and powerful preserve their riches and power, and whenever a law is passed for the purpose of helping the weakest in society, it will be manipulated to the advantage of the strongest. These problems are systemic and intractable because the powerful have the time and money to invest in keeping their stranglehold on the political system. No matter if they are monarchial, communistic, or democratic, governments all prop up some set of oligarchs. Link via Hit and Run. Filed under: Regulation, Unintended Consequences Comments: Comments Off on In Government, Every Day Is Opposite Day

|

|

Posted at 8:22 pm on June 18, 2010, by Wirkman Virkkala

As billions of gallons of “Texas Tea” bubble up into the Gulf of Mexico, I understand the rising tide of ill will directed against BP. The company’s smarmy, eco-friendly logo seems radically dissonant with the catastrophe they caused. And yet, demanding that the company pay for every dime of recovery, every opportunity squelched, every harm to life and property (as Rosie O’Donnell did, as many on the left are wont to do), this is a bit disingenuous, no? Filed under: Environment, Regulation Comments: 2 Comments

|

|

Posted at 11:19 pm on May 23, 2010, by Lee Sharpe

With the financial reform bill through both houses of Congress, it’s time to look at its contents, which do not look good at all for fans of limited government. Banks are taxed to pay for bailouts. Since banks will pass these taxes on to consumers, really it means bank customers (almost all Americans) will be paying for more bank bailouts. What those who take this view fail to see is that making banks “too big to fail” means that those banks will engage in as risky behavior as possible. Did their risks pay off? They keep the profits. Did the risks not pay off? That’s not on the banks, because the American public will be covering those losses instead. Ah, say the the more nuanced supporters of this legislation. That is this bill, to quote CNN:

How much risk is too much? I don’t know, neither does the governement, and probably the firms don’t know either. But if firms are all free to be as risky as they like — receiving the profits when they’re correct and being forced to endure the losses when they don’t (even at the risk of going bankrupt) — then the market will learn which risky behavior to avoid and which works. Instead government is guessing how much regulation is appropriate. Since the government (through creating expectations and in some cases guarantees of bailouts) is already encouraging banks to provide risky loans, if regulations don’t mitigate this enough, the banks have to be bailed out at the public’s expense. If the regulations mitigate this too much, reasonable loans that banks and recipients would both agree to the terms to will be banned by the government, slowing economic growth. Banks profiting from their investments is good for everyone. Home buyers and small business owners often need loans to succeed. Banks make more money in the long run, which they can use to make even more loans to others. Without the government’s help, this has been occuring to the mutual benefit of investors and loan recipiants. These home purchases and small businesses create direct and indirect employment. Having bankers and investors make their own choices and receive both the positive and negative consequences of their lending decisions is a much more effective way of doing that. It also doesn’t cost the public a thing. Filed under: Finance, Regulation Comments: Comments Off on Financial Reform

|

|

Posted at 3:57 pm on April 26, 2010, by Caitlin Hartsell

I came across this article about a U.K. think tank’s suggestion to improve British lives: Cap the work week at 21-hours. It’s brilliant reasoning, of course. The study found that people who work fewer hours have more time for fulfilling recreational activities; therefore, the government should mandate that people work less! At first I wasn’t sure if this study was serious, but I’ve since found that the New Economics Foundation is a real institute, established in 1986, which “aim[s] to improve quality of life by promoting innovative solutions that challenge mainstream thinking on economic, environment and social issues. We work in partnership and put people and the planet first.” On to the mocking! From the abstract of the study:

Ah yes, because before the Industrial Revolution, farmers and merchants worked about four hours a day, five days a week. The new work week would have people working the equivalent of two Industrial Revolution work days, when 10-12 hour days were typical. The study goes on:

If people are more productive, they should be compensated to reflect that. Indeed, we’ve seen a downward trend in average hours while the average standard of living has increased. These changes do not need governmental intervention to occur; if a company believes its employees are more efficient if they work fewer hours, then it would make financial sense for them to translate that into higher pay and decreased hours. To its credit, the study recognizes potential downsides of this policy. The article about the study says:

Not to mention, higher prices at the same time! To produce the same product or services, employers will either have to either pay overtime or hire more workers. An employee working 21 hours per week gains less experience than one working 30 or 40 hours; these employees on average are less efficient. This legislation, like minimum wage, makes the cost of labor more expensive, which will translate into higher prices. The NEF’s solution to these problems?

Ah, even higher prices! If a country is to achieve a 21 hour work week, it is because it has gotten so efficient that 21 hours are all that is necessary. (In fact, some people think you can get rich off a four hour work week, but that’s not for everyone.) Mandating a shorter work week does not achieve efficiency though. At any rate, more leisure time is not a good to be valued infinitely. As Henry Hazlitt explained in Economics in One Lesson, the increase in leisure time has diminishing marginal returns for the employee, while productivity decreases:

People don’t work just to work, but in part because increased income translates into higher standard of living and improved leisure time. Leisure activities necessitate money. The added anxiety of lower take home pay and higher prices would potentially outweigh the added benefits of further leisure time. Unfortunately, the NEF’s study does not thoroughly take into account the unintended consequences of their policy suggestion. Filed under: Economic Theory, Nanny State, Regulation, Unintended Consequences Comments: 1 Comment

|

| Next Page » | previous posts » |

The lesson here, though, is that when a government agency is tasked with protecting the public interest,

The lesson here, though, is that when a government agency is tasked with protecting the public interest,  When I was a kid, I loved watching

When I was a kid, I loved watching

"[T]he whole of economics can be reduced to a single lesson, and that lesson can be reduced to a single sentence. The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate but at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups."

"[T]he whole of economics can be reduced to a single lesson, and that lesson can be reduced to a single sentence. The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate but at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups."